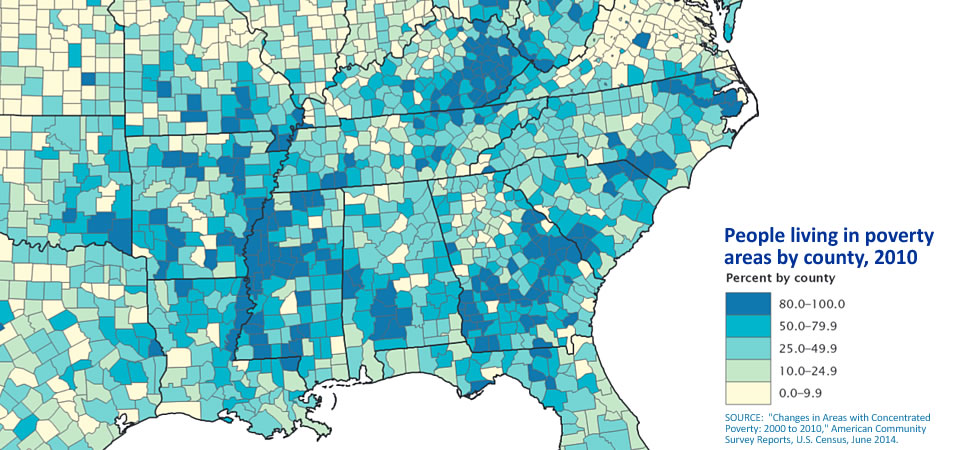

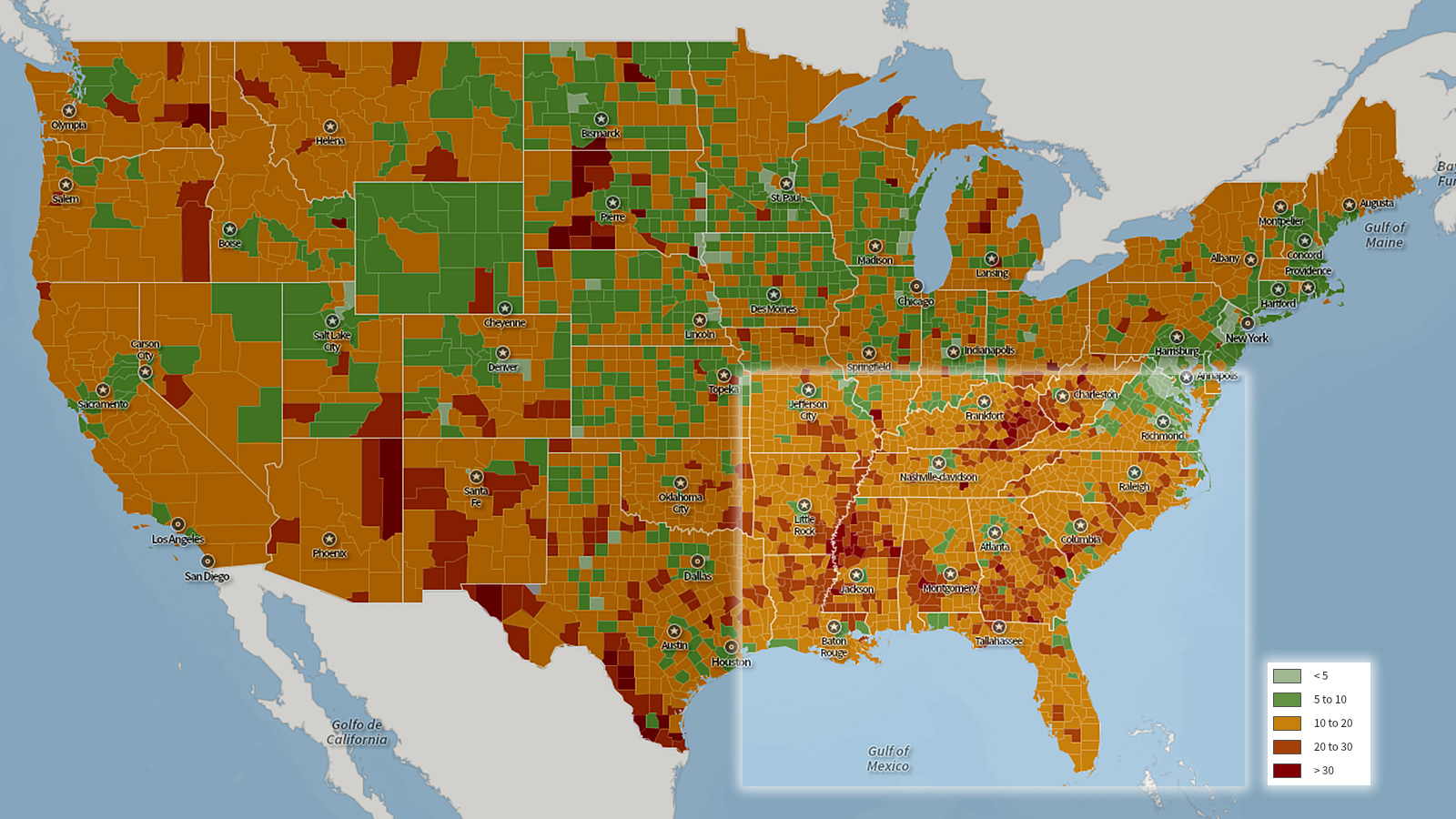

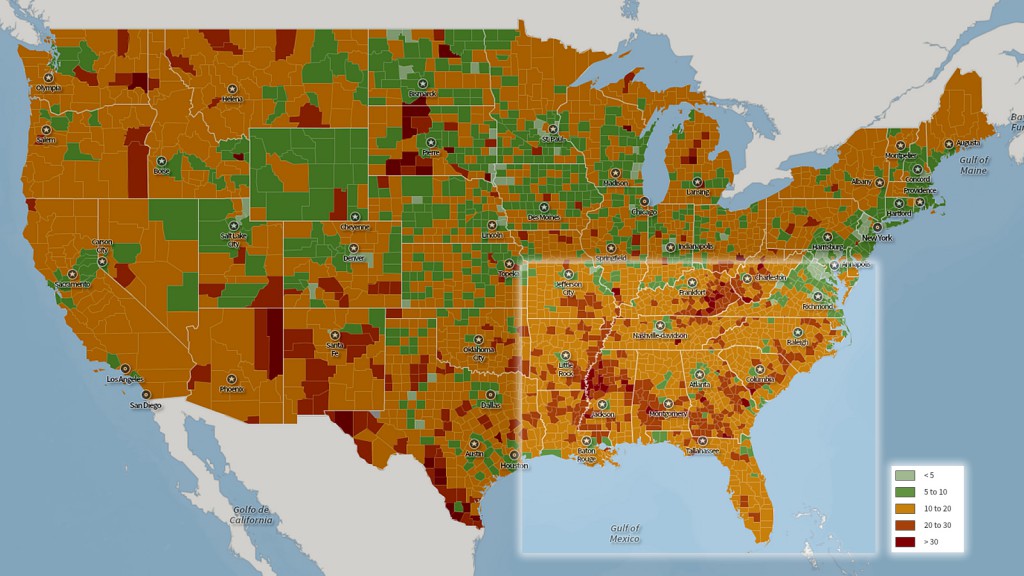

In late December, we met Travis Starkey, a Greenville, N.C., resident who is trying to focus attention on strategies to deal with endemic poverty of his part of eastern North Carolina — which fits right in with what the Center for a Better South seeks to do.

As the first post of the new year, we offer his 2013 photo of a green field near Roper, N.C., to highlight Starkey’s online effort, dubbed “Greenfield Southeast.” (Roper is a small town in rural Washington County, N.C. About 27 percent of Roper’s residents live at or below the federal poverty level; some 22 percent of Washington County’s residents are at or below poverty.

Here’s how he explained his blog in 2013, which has evolved over the last year and a half:

“Over the past year, I have spent hundreds of hours attempting to understand the depth of what the South is currently enduring educationally and economically, especially the rural South. Heartened by the increased attention being paid to education outcomes in cities like Nashville, Memphis, and New Orleans while also wary of the long-term viability of proposed improvements, I’ve moved forward – researching (and researching) and talking with anyone I can. I’ve also been inspired by technological innovations that could deepen learning and increase economic engagement in rural communities. Over time, though, my understanding of what would be truly helpful and should therefore be immediately acted-upon within either the education or economic space has grown increasingly unclear.

“Given all of this and the fact that I am now firmly planted in eastern North Carolina, I have decided to externalize this inner conversation in the hopes that doing so will bring clarity of purpose and action to me and others. With this blog, my hope is to bring attention to and instigate focused conversation around the unique educational and economic challenges facing citizens in the South, especially the rural South. There are numerous ways to frame the conversation; but I hope to frame it loosely around people, places, and ideas that are currently playing a role or could play a role in the continued progress of this region. And I aspire to write and engage not as an authority, but as a learner alongside many others whose thoughts and deeds will surely push the conversation forward.”

- Learn more about Greenfield Southeast | Visit on Facebook

- More about Roper, N.C., via Wikipedia

- More about Washington County, N.C.

Photo is courtesy Travis Starkey and is copyrighted 2013. All rights reserved.